After this lesson, students will be able to:

- Cite examples of Rome’s contributions to the Silk Road.

- Make connections between the diets of historic cultures and foods we eat today.

- Understand how the cooking process impacts the resulting product.

During this lesson, students will:

- Answer questions about the spread of Roman ideas, goods, and food along the Silk Road.

- Learn that noodles and pasta were important foods in ancient Rome and China, and will describe their favorite way to eat noodles or pasta.

- Carefully follow a precise process to make handmade noodles from scratch, and compare the taste and consistency of the handmade noodles with store-bought pasta.

INGREDIENTS

-

Pasta flour

Equipment

- Stove

Tools

- Stockpot

- Mixing bowl

- Zester

- Grater

- Crinkle cutter

- Spider strainer

- Pasta crimper

- Rolling pins

- Bench scraper

- Chef’s knives

- Paring knives

- Cutting boards

- Measuring cups

- Measuring spoons

- Forks

BEFORE YOU BEGIN

- Collect all the tools and ingredients, and then distribute them to the tables.

- Gather supplies for the Chef Meeting.

- Create the visual aid.

- Copy the Homemade Hand-Rolled Pasta recipe to hand out.

- Copy the Gremolata recipe to hand out.

- Prepare pasta dough (if possible, use dough made in an earlier class).

AT THE CHEF MEETING

Welcome students and introduce Rome as the final stop on their Silk Road journey.

- Today we're going to learn how silk made it to Rome and almost made the Roman Empire go broke.

- Remind students of the long trip through China and India, and ask for examples of important goods, ideas, and foods from each region that were traded on the Silk Road. Have students recall the foods they prepared in class when studying those regions.

- Explain that Rome was one of the most powerful empires in the history of the Western world. It began in Italy and expanded to include most of Europe, North Africa, Egypt, and Syria over a period of 500 years.

- The Roman Empire became part of the Silk Road 200 years after China. And the Romans were absolutely crazy about silk.

- Our story begins after the treaty between the Chinese and Xiongnu in 198 BC in which Emperor Gaozu gave his daughter to the Xiongnu and began to pay an annual gift in gold and silk.

- Silk gradually made its way to Rome. The Xiongnu traded it to the Yuezhi, who traded it with the Parthians, who traded it with the Romans.

- The Romans were crazy for silk—it was a status symbol and everyone had to have it, even just a small patch to pin to their clothes. But after being traded by so many people, it was very expensive and it became a drain on the Empire.

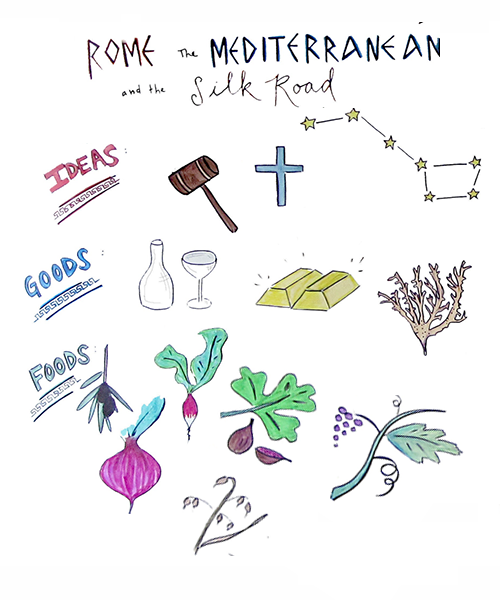

- Prompt students to use the visual aid: What were some of the goods traded by the Romans for silk?

- The Romans started spending so much gold on silk that by 14 CE Emperor Tiberius actually introduced a ban on silk to try and rein in Roman spending.

- The Romans wanted to make silk themselves, but the Chinese carefully guarded the secret of how to make silk because it was a source of great wealth for their empire.

- Buddhism was not the only religion to spread along the Silk Road. Christianity also came by way of missionaries from the Roman Empire (and Islam from the Middle East, though not until later).

- In 552 CE, two Assyrian Christian monks visited China, learned the secret of silk, and smuggled out silkworms and mulberry seeds in their walking sticks (Assyria was at this time a province of the Roman Empire).

- The Romans could then make their own silk, though it was never of the same quality as that made by the Chinese.

- Today we are making Homemade Hand-Rolled Pasta with Gremolata. Noodles, like silk, originated in China and came to Italy by way of the Silk Road where they became very popular. Today we are making an Italian version of the Chinese-originated dish.

- Review the recipes and demonstrate how to make the dough directly on the table or in a mixing bowl.

- Ask students to wash their hands and join their table group.

AT THE TABLE

Review and prepare the recipe.

- Small-group check-in: What is your favorite way to eat noodles or pasta?

- Review the recipes.

- Divide into three working groups:

- The first group of students rolls, cuts, and cooks the pasta using previously prepared pasta dough.

- The second group of students prepares pasta dough for the following class.

- The third group of students grates cheese and prepares the gremolata.

- Set the table; eat; clean up.

AT THE CLOSING CIRCLE

Students reflect on the recipe.

- Ask students to use their fingers to rate the recipe on a scale of 1 to 5.

- If there is time, challenge students to refer to the foods depicted in the China, India, and Rome visual aids to brainstorm dishes they eat today that may have been traded along the Silk Road.

- Kneading

- Cultural Influence

- Gluten

- Zesting

- Status Symbol

- Boiling the water: Don't forget to set pots on to boil early so that the water can be at a rolling boil as soon as the pasta is ready to be cooked.

- Dough: We made four batches of dough with each class of about 30 students (each of the three table groups made one batch, and we made a sample batch as part of the Chef Meeting at the beginning of class).

- Pay it forward: This dough needs at least 20 minutes to rest and can rest overnight in the fridge (it rolls best when warm, so it is best to give it at least 15 minutes to warm up at room temperature if you keep it in the fridge). We use the pay-it-forward model by having each class make dough for the following class. We made four batches of dough before the first class in the rotation.

- Flour: Every table should have its own container of flour to minimize mess and make more flour easily accessible to keep the dough from getting too sticky.

- Science of pasta dough: We found that explaining the “why” behind the dough-making process helped our students to make more successful pasta. You let the dough rest so that it’s not too tough and won't crack when you try to roll it out. The dough only has to rest 20 minutes, and beyond that, more resting doesn't considerably change the consistency. You mix the wet and dry ingredients together relatively slowly as opposed to dumping them all in a bowl at the same time in order to avoid big clumps and get the smoothest possible dough, but you don't have to mix so slowly that it's a grain of flour at a time.

- Kneading: We reference the Pan de los Muertos lesson that the sixth graders did in the fall to remind them of kneading technique. We explain that you don't want the dough sticky, but you want to add as little flour as you can get away with to keep it from getting sticky. Your goal with kneading is to produce a smooth texture, so you don't want to tear the dough (you want to organize the proteins in the flour into a neat structure, which tearing disrupts. This highly organized protein structure is what yields the best texture for pasta).

- Rolling the dough: The dough should be rolled very thin. This is most easily done if the recipe is portioned into at least four or more pieces as opposed to being rolled as one large piece.

- Pass-it-on rolling technique: We generally break students into three groups to complete this recipe: making dough, rolling dough, and making gremolata. The dough makers and gremolata makers will likely finish in time to also have a turn to roll out and cut dough. Have students who rolled the first few pieces of dough teach the students who start later. Tell the first rollers that this will happen so they can practice perfecting their technique and plan how they'll teach their classmates.

- Cutting the pasta: We cut our pasta with roller cutters, bench scrapers, or a knife on the cutting board. With roller cutters, it's important to press firmly and roll one way in order to get the cleanest cut. In terms of shape, there are a million ways to cut pasta and every single one is delicious. A favorite of our students is making bowties, by cutting out rectangles and then crimping the middles.

- Zesting: We like to challenge students to try to keep the lemon the same shape, just turn it from yellow to white by removing just the zest and not the bitter pith.

- Putting it all together: There are many ways to assemble the gremolata, cheese, olive oil, salt, and pasta for the final dish. We found the gremolata tastes best if you massage the parsley, lemon zest, and garlic with salt, then toss it with oiled pasta, then put cheese on top. Students also love to just throw little bits of each component into the bowl as the pasta comes out of the pot and assemble the dish little by little.

- Dietary restrictions: We always keep gluten-free and vegan versions of the recipe on hand for students who may need them.

Academic Standards

English Language Arts and Literacy, Grade 6

Engage effectively in a range of collaborative discussions (one-on-one, in groups, and teacher- led) with diverse partners on grade 6 topics, texts, and issues, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly.

History – Social Science, Grade 6

Cite the significance of the trans-Eurasian “silk roads” in the period of the Han Dynasty and Roman Empire and their locations.

Edible Schoolyard Standards

Terms & Techniques

Use basic cooking terms and techniques.

Tools

Identify and name basic tools and equipment.

All lessons at the Edible Schoolyard Berkeley are developed in collaboration with the teachers and staff of the Edible Schoolyard and Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School.